Metacognitive Reflection in the Language Classroom

Metacognitive reflection helps students understand how they learn and strengthen learning over time. When reflection is built into instruction and designed through a UDL lens, students use feedback and retrieval to build confidence, reduce anxiety, and learn more independently.

Pause, Reflect, Grow: Making Metacognition Work in the Language Classroom through the lens of Universal Design for Learning

For years, I've ended the last five minutes of class on Thursday or Fridays with a simple prompt:

“What’s working for you? What’s not? Anything you want me to know? Any plans for the weekend?”

I found myself skimming over everything else; my favorite thing to read was what students actually had to say about their learning and our activities that week. Their feedback often included small, thoughtful suggestions that helped me fine-tune lessons or repeat activities that worked the following week.

Over time, I realized that reflecting once a week wasn’t enough. I began inviting students to pause before, during, and after learning to think about what was working for them and what wasn’t. I talked explicitly with them about how they learn, not just what they were learning.

And it’s working.

In my mid-year survey, my students appreciated these moments of reflection. Many shared that the pauses helped them approach learning more intentionally, and some noted that reflection helped them feel less overwhelmed and more in control. What they were doing, often without realizing it, is what researchers call metacognitive reflection.

Metacognitive reflections are moments when students think about their own thinking and learning.

In simple terms, it’s when students ask themselves:

How did I learn this? What helped me? What was hard? What will I do next time?

These moments help students make sense of their learning, recognize growth, and set goals. But reflection isn’t one-size-fits-all. Students reflect best in different ways. That’s where Universal Design for Learning (UDL) comes in: by offering multiple ways to reflect, teachers remove barriers and invite every student to engage meaningfully in metacognition.

What Research Says About Metacognition in Language Learning

Metacognition, or students’ awareness of how they learn, significantly improves language acquisition, especially when paired with explicit reflection and strategy use (Martelletti, Luzuriaga, & Furman, 2023; Sur, 2025).

1. Metacognition Improves Language Proficiency

Studies consistently show that learners who:

- Plan how they will approach a task

- Monitor comprehension while listening or reading

- Reflect on what worked afterward

→ perform better in reading, listening, speaking, and writing than learners who don’t.

Students who know how they learn vocabulary and concepts can reflect on what’s working, adjust strategies, and use retrieval practice to strengthen and retain their learning over time.

2. Strategy Awareness Matters More Than “Talent”

Studies by Oxford (2003), Wenden (1998), and more recent meta-analyses (Sur, 2025) show that metacognitive strategy awareness, not innate talent, is one of the strongest predictors of language success.

Successful language learners:

- Use strategies intentionally

- Monitor their understanding and adjust when needed

- Reflect on errors without shutting down

In other words, they don’t interpret difficulty as failure, but rather as feedback.

Metacognition helps students shift from:

“I’m bad at languages”

to

“This strategy didn’t work. What can I try next?”

When students learn that success comes from strategy use, not ability, confidence grows, and anxiety decreases (Dörnyei, 2005).

3. Metacognitive Reflection is Especially Powerful for Listening and Reading

When students reflect on how they listen or read, they become more strategic and intentional learners. For example, I have my students follow along with their pointer finger or the pointy part of a feather as they listen, notice repeated words or key phrases, or silently predict what might come next. While reading, they might skim a text first for the main idea, highlight or underline important details, or skip unfamiliar words strategically instead of freezing.

These strategies help students:

- Focus on meaning rather than translating word-for-word

- Predict, check understanding, and tolerate ambiguity

- Sustain comprehension over longer passages instead of getting stuck on one detail

These skills are critical for real-world language use. Studies on inferential reading demonstrate that metacognitive reflection improves students’ ability to sustain comprehension over time, not just answer immediate questions correctly (Martelletti et al., 2023).

4. Reflection Reduces Anxiety & Increases Risk-Taking

Metacognitive practices don’t just improve academic outcomes; they also support students emotionally.

Research shows that reflection:

- Lowers language anxiety

- Increases willingness to speak

- Improves persistence when tasks feel difficult

When students pause and reflect regularly, mistakes become data, not failure. This reframing encourages risk-taking and keeps students engaged even when language feels challenging (Dörnyei, 2005; Alolaywi, 2025).

5. Metacognition Works Best When Explicit

I learned this firsthand when a I observed a student stared blankly at a reading passage. I modeled my own thinking aloud: “When I don’t understand a word, I look at the surrounding words and try to guess the meaning. If that doesn’t work, I move on and come back later.” Metacognition does not happen automatically; it must be taught and modeled.

Research is clear: students benefit most when teachers explicitly show them how to reflect (Wenden, 1998; Sur, 2025).

Effective classrooms:

- Model thinking aloud (“Here’s what I do when I don’t understand…”)

- Use short, frequent reflection moments, even 30–60 seconds

- Keep reflection language simple and concrete, especially for Novice learners

Small, consistent reflection practices lead to meaningful gains.

6. Strong Alignment with ACTFL & UDL

Metacognitive reflection also supports broader frameworks:

- ACTFL Can-Do Statements: students assess their own progress

- UDL: multiple ways to reflect and express understanding

- SEL: self-awareness and self-management

Ok, I get it, metacognitive reflections are a big deal. But how do I actually make room for them in my classroom without adding a ton of extra work?

Here’s the thing: reflection isn’t one-size-fits-all. When you teach students how to think about their thinking, and pair it with retrieval practice, they don’t just remember more, they begin to take ownership of their own learning.

And here’s what hit me: reflection can’t just be a once-a-week “thing.” It has to live in your classroom every day.

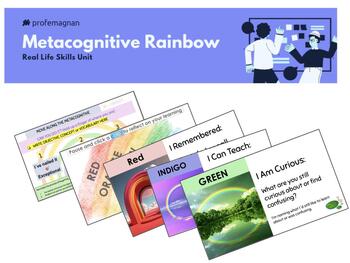

Next post, I'll share how I made metacognitive reflections easy, fun, and totally habit-forming 🚪✨

References

Alolaywi, Y. (2025). The role of metacognitive strategies in enhancing EFL learners’ academic success. Forum for Linguistic Studies.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Martelletti, D. M., Luzuriaga, M., & Furman, M. (2023). “What makes you say so?” Metacognition improves the sustained learning of inferential reading skills in English as a second language. Trends in Neuroscience and Education, 33, 100213.

Oxford, R. L. (2003). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. GALA, 1–25.

Sur, E. (2025). The role of metacognitive strategies training in foreign language learning: A meta-analysis study. Journal of Ahmet Kelesoglu Education Faculty, 7(1), 1–13.

Wenden, A. (1998). Metacognitive knowledge and language learning. Applied Linguistics, 19(4), 515–537.

Zou, X., & Tang, Y. (2024). Examining metacognitive strategy use in L1 and L2 task-situated writing: Effects, transferability, and cross-language facilitation. Metacognition and Learning, 19, 773–792.