The Power of Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is one of the most effective ways to strengthen memory and learning. Discover how bringing information back to mind improves long-term retention and supports student success.

Psychologist Dr. Stuart Ablon (Harvard and Mass General Brigham) summarizes his approach to learning with six words: “Kids do well if they can.” He emphasizes that when students struggle, it’s often due to a lack of skill, not motivation.

This perspective is especially relevant in language classrooms. Ablon’s framework helps us shift from blame to understanding: if students aren’t retrieving language, it’s not because they aren’t trying, it’s because they need more structured opportunities to build those memory pathways.

This is where the science of learning, particularly retrieval practice, becomes essential. It gives students the repeated, low-stakes chances they need to strengthen memory, fill skill gaps, and actually use the language we’re teaching.

The Paradox of Forgetting

Forgetting is a natural process that prevents cognitive overload, keeping our brains from being overwhelmed by constant input. Forgetting keeps us sane! However, forgetting presents a challenge for educators. Even when students pay attention and practice, much of what they learn can fade quickly.

According to the forgetting curve, learners may forget more than half of new information within an hour and nearly two-thirds within 24 hours (Ebbinghaus, 1885).

The solution: deliberate retrieval, combined with creating a desirable difficulty for students. Each time students actively recall information, even once, their retention improves. Adding meaningful context, such as stories, visuals, movement, or connections to prior knowledge, reduces the number of repetitions needed. Forgetting and relearning isn’t just normal; it’s how learning becomes lasting.

Myth vs. Fact: Effortful Learning Matters

Myth: If students learn something easily, they’ll remember it.

Fact: Easy learning often creates an illusion of mastery. Real learning sticks when it feels effortful.

Research shows that retrieval that challenges the mind, a “desirable difficulty” (Agarwal & Bain, 2019), strengthens memory and deepens understanding. Cramming produces short-term gains, but strategies like spaced retrieval, interleaving, and varied practice support lasting learning.

Evidence-Based Strategies That Work

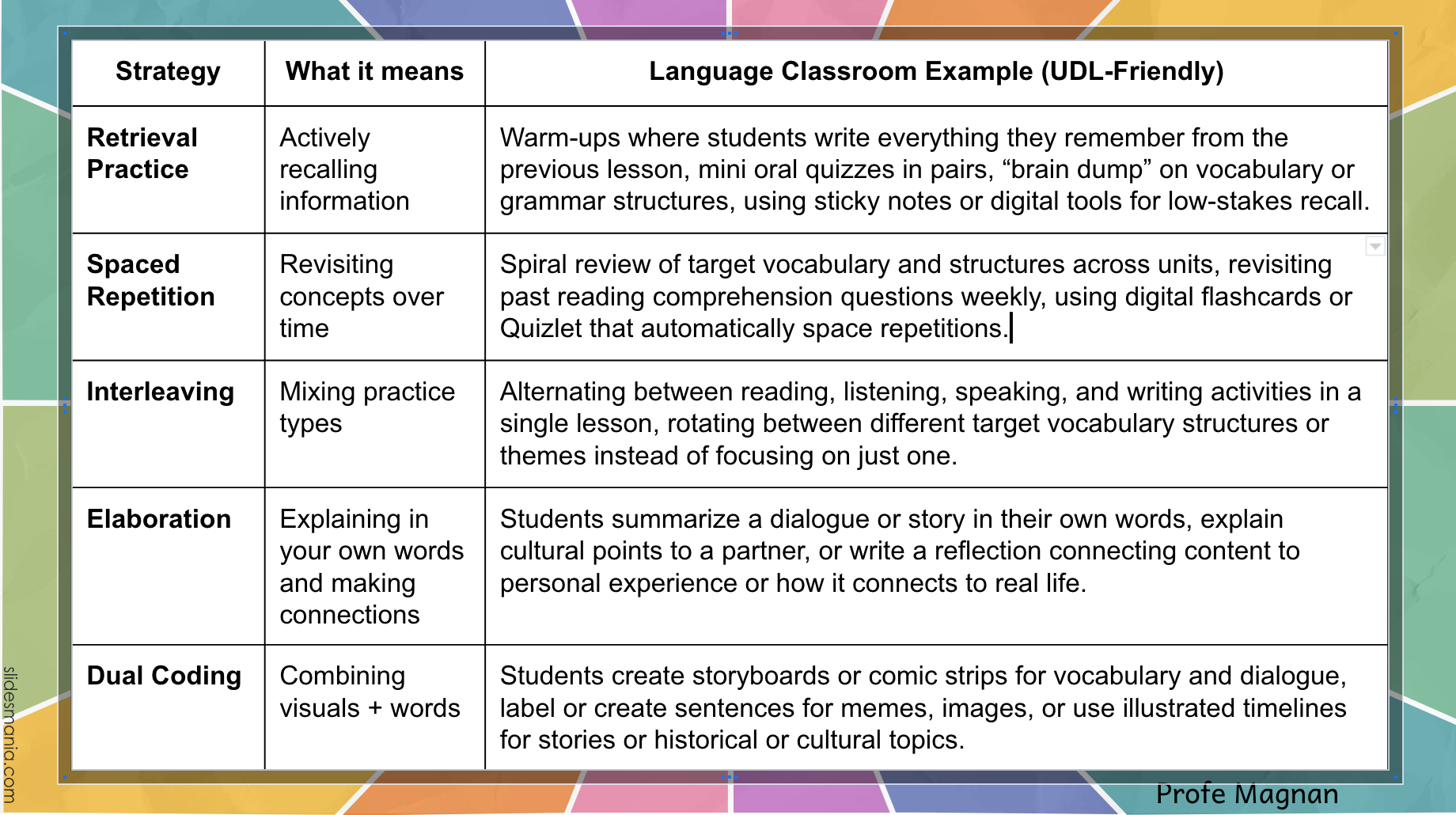

Retrieval, Spaced Practice, and UDL in the Language Classroom

Research from the science of learning shows that active retrieval, spacing, interleaving, elaboration, and dual coding strengthen memory and long-term learning. In the language classroom, these strategies are even more powerful when paired with Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles, giving students multiple ways to access, engage with, and express their knowledge. Below are practical ways to implement these strategies:

UDL Tips for Retrieval and Memory (SLA-Informed)

1. Multiple Means of Engagement

Help students stay motivated and make learning meaningful by letting them choose topics, partners, or how they show what they know. Motivation matters, a lot, for second language learning (Dörnyei, 2005; Dörnyei & Ryan, 2015; MacIntyre et al., 2019). When students connect what they’re learning to their own lives or interests, they pay more attention, practice more, and remember more.

Working with partners or in groups also gives students a chance to speak and get feedback, which strengthens both memory and language skills (Swain, 2005). Plus, it naturally encourages them to recall and use language multiple times, helping it stick.

Practical Ways to Try This in Class

- Pair a dialogue with a short video, labeled images (I use screenshots with key vocabulary or questions), or slides so students can see, hear, and interact with the language.

- Combine a written dialogue with an audio recording.

- Drawing and a simple storyboard. Different ways of experiencing the same content help students remember vocabulary and phrases.

- Let students pick their topic, partner, or format for a task such as a skit, poster, digital story, or short presentation.

- Have students work together to summarize a scene, teach each other new words, or compare cultures. This gives them repeated practice and helps language stick.

By giving students choice and making lessons interactive, you boost attention, motivation, and memory, making language learning more effective and more fun for everyone.

2. Multiple Means of Representation

Provide content through visuals, text, audio, or interactive media. Recent SLA research shows that multimodal input helps learners notice language forms, link meaning to context, and improve retention (VanPatten & Benati, 2015; Plonsky, 2018). For example, pairing an authentic dialogue with a short video clip, labeled images, or interactive slides supports comprehension and vocabulary retrieval, giving learners several pathways to encode and remember language.

Practical Way to Try This in Class

- Pair a written text, dialogue, or reading with an audio recording so students can see and hear the language.

- Add a short video clip that shows the conversation in context, giving meaning to the language.

- Create an illustrated storyboard or labeled images to help students visualize vocabulary and actions. You can have students cut the images out and put the story in order.

- Use interactive slides or digital tools that let students manipulate language, such as dragging words to match images or sequencing a story.

- Combine these approaches: for example, students read a dialogue, listen to it, watch a short clip, and then summarize the story using images or a storyboard.

By presenting language in multiple ways, you give students repeated exposure, help them connect new words and structures to context, and make language learning more memorable and accessible.

3. Multiple Means of Action and Expression

Let students show what they know in different ways—speaking, writing, drawing, or using digital tools. SLA research shows that giving learners multiple ways to produce language encourages comprehensible output, helps them notice gaps in their knowledge, and strengthens memory (Swain, 2005; Plonsky, 2018).Research highlights that output and production facilitate noticing, strengthen memory traces, and promote transfer to new contexts (Lyster & Saito, 2010; Izumi, 2020). Providing two options reduces cognitive overload and lets learners engage with language in ways that suit their strengths while reinforcing retrieval and practice.

Practical Ways to Try This in Class

- Have students write or draw to re-tell a story learned in class.

- Allow them to use what they wrote or draw to verbally share the story with a classmante or verbally record their response.

- Encourage peer feedback: students can give each other tips or ask questions about language use.

- Offer choice: students decide whether to present a story orally, visually, or in writing, based on their strengths.

By providing multiple ways to act on language, students deepen understanding, retain vocabulary and structures longer, and feel more confident in their abilities.

For more ideas on Retrieval Practice into action, check out my Edutopia article: https://www.edutopia.org/article/retrieval-strategies-middle-high-school

References

Agarwal, P. K., & Bain, P. M. (2019). Powerful teaching: Unleash the science of learning. Jossey-Bass.

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual differences in second language acquisition. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of the language learner revisited. Routledge.

Ebbinghaus, H. (1885). Memory: A contribution to experimental psychology.

Izumi, S. (2020). Output-based instruction. In S. Loewen & M. Sato (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of instructed second language acquisition (pp. 231–247). Routledge.

Lyster, R., & Saito, K. (2010). Oral feedback in classroom SLA: A meta-analysis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 32(2), 265–302. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263109990520

MacIntyre, P. D., Mackinnon, S. P., & Clément, R. (2019). Willingness to communicate and motivation. In S. Mercer & T. Kostoulas (Eds.), Language teacher psychology (pp. 53–71). Multilingual Matters.

Novak Education. (2024). Holistic, single-point, and analytic rubrics. https://www.novakeducation.com/blog/holistic-single-point-and-analytic-rubrics

Plonsky, L. (2018). Experimental and quasi-experimental research in second language acquisition. Routledge.

Sense & Sensation. (2013). How people learn: Cognitive model for education. http://www.senseandsensation.com/2013/03/how-people-learn-cognitive-model-for.html

Swain, M. (2005). The output hypothesis: Theory and research. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning (pp. 471–483). Routledge.

VanPatten, B., & Benati, A. G. (2015). Key terms in second language acquisition. Routledge.